Our Strategic Blueprint

I took on the CEO role last year because I see QuantumScape as the global leader in solid state battery technologies with an ability to revolutionize energy storage and create tremendous shareholder value in the process.

When discussing energy density, there is a lot of focus on the individual layers of the battery where the fundamental electrochemistry happens. These repeating layers of cathode– separator–anode can be thought of as the active stack. Incorporating higher electrode loading or more energy-dense chemistry will improve the energy density of the active stack and the entire battery.

But there’s more to the energy density of a cell than just the stack energy density. After all, batteries aren’t sold as naked stacks of active material but as fully packaged units. And how the active stack is packaged plays an important role in the overall energy density. In this blog article, we will examine a few ways that inactive materials and packaging efficiency affect cell energy density.

A major driver of improved energy density over the past decade has nothing to do with better chemistry or new materials, but rather improvements to manufacturing that allow battery makers to pack more active material into the same size cell. Higher-precision machinery and refined manufacturing techniques can minimize waste inside the cell package.

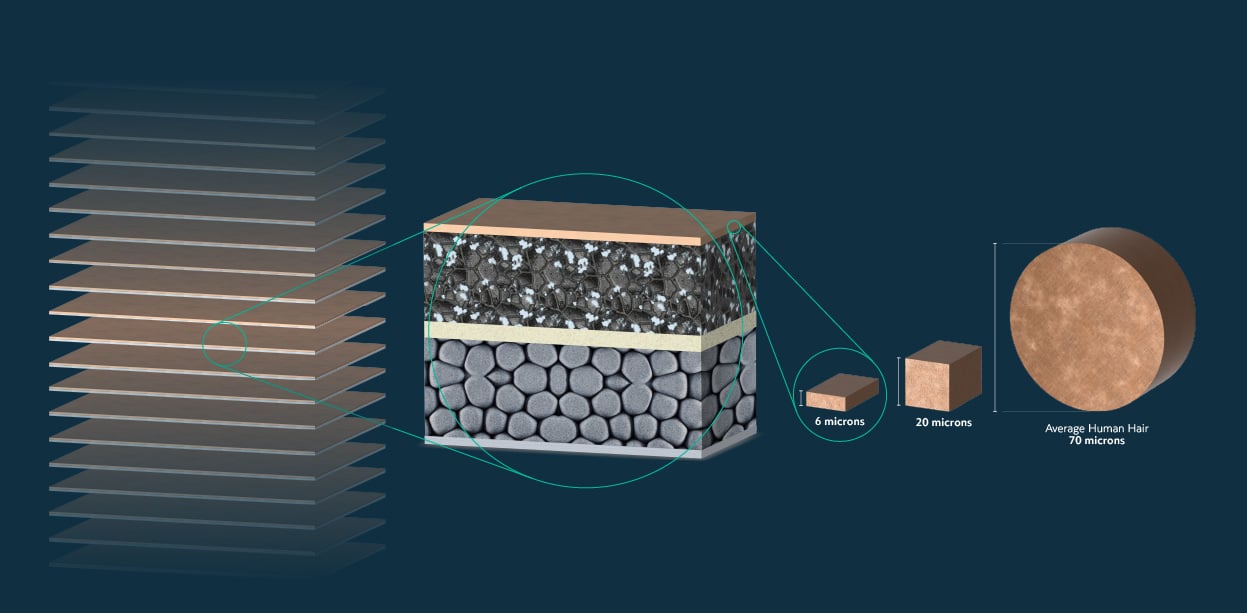

For example, consider how a cathode is made. High-energy nickel-based cathode active material is a fine metal oxide powder mixed with a liquid and coated onto a sheet of thin metal foil, similar to the aluminum foil you can find in your kitchen. This foil is called the current collector; aluminum foil is used for the cathode and copper foil for the anode.1

Although the current collector is an essential component, conducting electrons and heat out of the battery, the collector itself is inactive material with respect to the reactions that deliver energy from the battery; essentially, it’s dead weight from the point of view of energy density. Therefore, an obvious way to pack more energy into a battery is to reduce the thickness of these current-collector foils.

Modern current-collector foils are much thinner than they were 20 years ago. For example, copper anode current collectors have shrunk from 20 microns to as little as 6 microns in thickness. These are not insignificant changes – copper foil alone was once nearly 20% of the mass of the whole battery, but it’s now ~6%.

Using a copper foil that is 3x thinner is more challenging though from a manufacturing perspective – thinner foils are harder to handle and tear more easily. But as the lithium-ion battery industry has matured, it has found solutions to these problems, and significantly improved energy density in the process.

But such improvements also have limits. By going from 20 to 6 microns, battery makers have shaved off 14 microns of thickness, but it would be impossible to remove another 14 microns from a current collector that is only 6 microns thick. Thinner current collectors would also negatively impact the cell’s electrical conductivity and thermal performance. As such, changes to the current collectors are beginning to show diminishing returns.

Whether using thinner current collectors, making sure everything fits more precisely together or removing empty spaces inside the cell package, battery makers have already significantly optimized conventional lithium-ion battery design. But that’s not the only way to squeeze more energy density from existing technology.

Another way to improve packaging efficiency exploits a simple principle of geometry: as you make an object larger, its volume grows faster than its surface area.2 So, if you need to package a larger volume, the ratio of packaging to volume will decrease as the enclosed volume grows. That statement may seem abstract or even a bit confusing, but the connection to energy density is easy to illustrate.

Imagine two bottles of water: a one-liter bottle and a two-liter bottle. Of course, the two-liter bottle holds twice as much as the one-liter bottle; it has double the volume. But if you weighed each bottle, you’d find that the one-liter bottle weighs ~36 grams, while the two-liter weighs ~47 grams – only about 30% heavier, not twice as heavy. So, while a one-liter bottle can hold one liter of water per 36 grams of packaging, a two-liter bottle can hold one liter per 23.5 grams of packaging. In other words, two-liter bottles have better packaging efficiency simply because they’re larger.

The same basic principle applies to batteries. Just like a bottle of water, the packaging material contributes to the overall weight of the battery, and if the battery is very small, the dead weight of the packaging will be a considerable fraction of the battery’s total weight, reducing its final energy density. Simply by making the battery larger, the ratio between the packaging and the active material inside the volume of the battery will decrease.

This is the logic behind pursuing larger and larger battery cells, particularly LFP cells: LFP chemistry suffers from poor energy density, so cells must be made much larger to compensate for that deficiency. Some of today’s largest LFP cells tip the scales with capacities of more than 100 Ah; compare this to smartphone batteries, which are typically 3–4 Ah in capacity.3

Making bigger cells to improve energy density is not a straightforward solution to the energy density challenge, its a workaround that can ameliorate some of the limitations of conventional active materials. And this workaround has its own set of serious drawbacks – most importantly, batteries can only be made so large before reliability and safety concerns begin to arise. Achieving uniformity, managing heat, and preventing catastrophic thermal runaway all become much more difficult in a larger-volume cell. Thermal runaway, when a localized failure in a cell causes a temperature rise that heats neighboring cells, resulting in a cascading failure of the entire pack, is especially a concern for those conventional lithium-ion cells that use more volatile high-performance nickel-based chemistries. These are some of the reasons why the 2170 cylindrical battery cells,4 with roughly 4–5 Ah capacities, are still some of the most energy-dense conventional batteries available in today’s EVs.

Additionally, for applications like consumer electronics, bigger size is often not an option because larger batteries won’t fit inside the thin housings that make modern smartphones or laptops so appealing. In short, bigger isn’t always better.

Yet these approaches are beginning to run out of juice. There is only so much inefficiency you can wring out of packaging, and most of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. At the end of the day, optimizing packaging is important, but we believe the most promising way to drive long-term improvements to energy density is with next-generation battery chemistry, such as QuantumScape’s solid-state lithium-metal technology.

[1] While copper is much heavier than aluminum, it’s generally not possible to use aluminum as the anode current collector in conventional lithium-ion batteries, since aluminum is not stable against lithium at low voltages. This means that lithium ions would be pulled into the aluminum, damaging the battery. In contrast, copper does not alloy with lithium.

[2] This is known as the Square-Cube Law

[3] www.phonearena.com/news/apple-iphone-13-series-battery-capacities-leaked_id132514

[4] The 2170 cylindrical cell, used in several leading EVs, is named for its dimensions: 21 mm wide and 70 mm in length. It’s sometimes called a 21700 if height is given in tenths of millimeters, as in the earlier 18650.

Special thanks to Liz Robb for research assistance

Forward-Looking Statements

This article contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the federal securities laws and information based on management’s current expectations as of the date of this current report. All statements other than statements of historical fact contained in this article, including statements regarding the future development of QuantumScape’s battery technology, the anticipated benefits of QuantumScape’s technologies and the performance of its batteries, and plans and objectives for future operations, are forward-looking statements. When used in this current report, the words “may,” “will,” “estimate,” “pro forma,” “expect,” “plan,” “believe,” “potential,” “predict,” “target,” “should,” “would,” “could,” “continue,” “believe,” “project,” “intend,” “anticipates” the negative of such terms and other similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements, although not all forward-looking statements contain such identifying words.

These forward-looking statements are based on management’s current expectations, assumptions, hopes, beliefs, intentions, and strategies regarding future events and are based on currently available information as to the outcome and timing of future events. These forward-looking statements involve significant risks and uncertainties that could cause the actual results to differ materially from the expected results. Many of these factors are outside QuantumScape’s control and are difficult to predict. QuantumScape cautions readers not to place undue reliance upon any forward-looking statements, which speak only as of the date made. Except as otherwise required by applicable law, QuantumScape disclaims any duty to update any forward-looking statements. Should underlying assumptions prove incorrect, actual results and projections could differ materially from those expressed in any forward-looking statements. Additional information concerning these and other factors that could materially affect QuantumScape’s actual results can be found in QuantumScape’s periodic filings with the SEC. QuantumScape’s SEC filings are available publicly on the SEC’s website at www.sec.gov.

I took on the CEO role last year because I see QuantumScape as the global leader in solid state battery technologies with an ability to revolutionize energy storage and create tremendous shareholder value in the process.

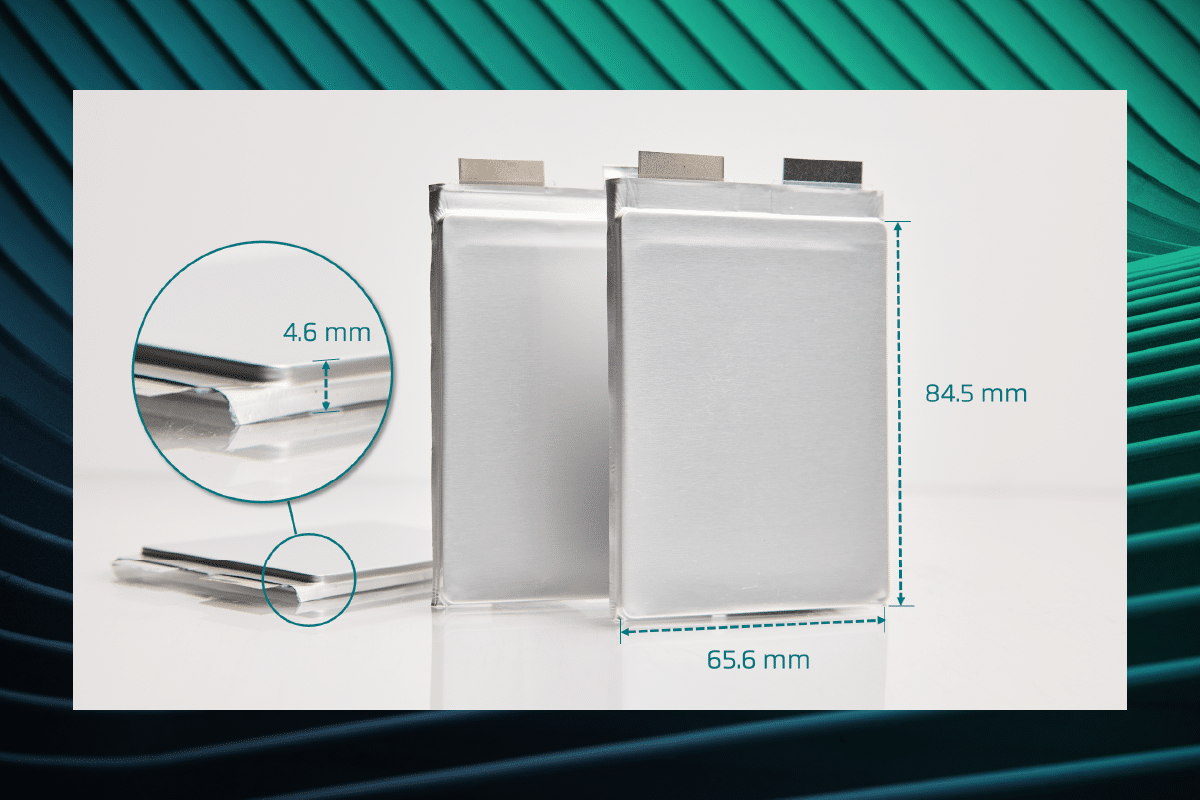

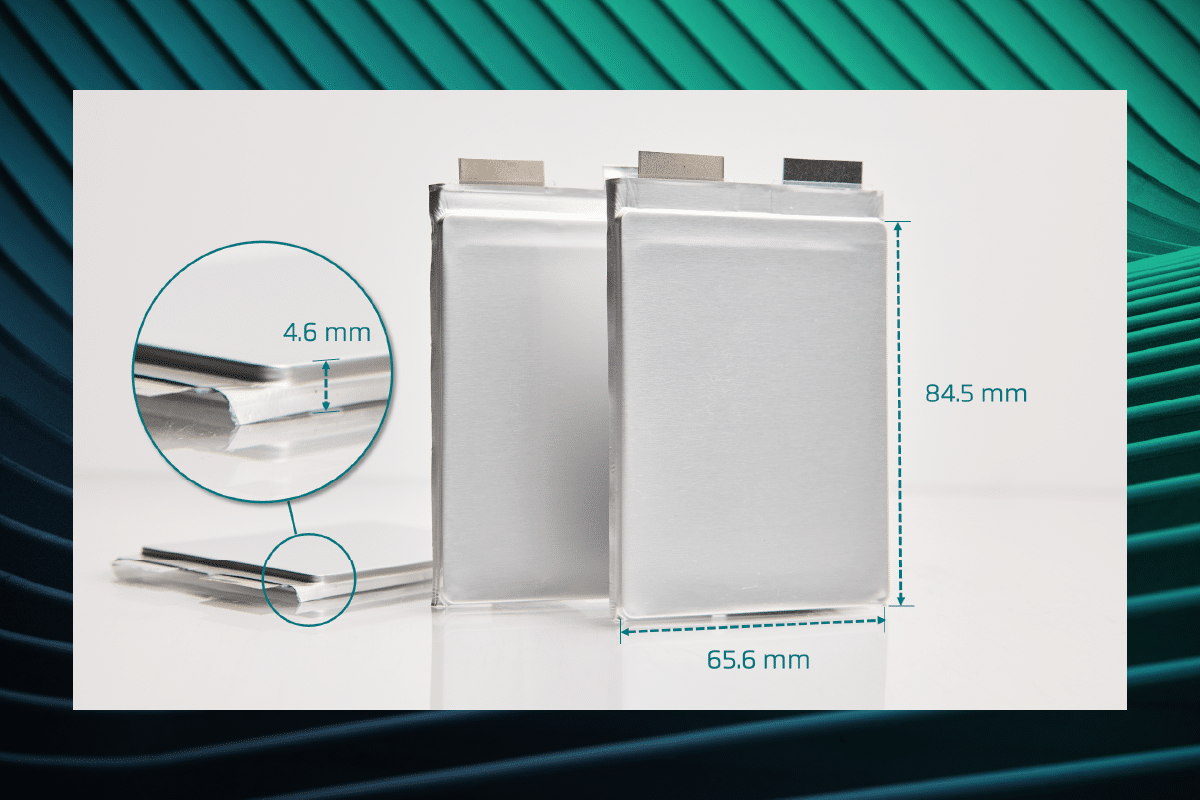

QuantumScape’s planned first commercial product, QSE-5, is a ~5 amp-hour cell designed to meet the requirements of automotive applications. Here, we’ll walk through the various elements of the cell specifications and explain some of the complexities behind the seemingly simple metric of energy density.

I took on the CEO role last year because I see QuantumScape as the global leader in solid state battery technologies with an ability to revolutionize energy storage and create tremendous shareholder value in the process.

QuantumScape’s planned first commercial product, QSE-5, is a ~5 amp-hour cell designed to meet the requirements of automotive applications. Here, we’ll walk through the various elements of the cell specifications and explain some of the complexities behind the seemingly simple metric of energy density.

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

© 2025 QuantumScape Battery, Inc.

1730 Technology Drive, San Jose, CA 95110

info@quantumscape.com

Pamela Fong is QuantumScape’s Chief of Human Resources Operations, leading people strategy and operations, including talent acquisition, organizational development and employee engagement. Prior to joining the company, Ms. Fong served as the Vice President of Global Human Resources at PDF Solutions (NASDAQ: PDFS), a semiconductor SAAS company. Before that, she served in several HR leadership roles at Foxconn Interconnect Technology, Inc., a multinational electronics manufacturer, and NUMMI, an automotive manufacturing joint venture between Toyota and General Motors. Ms. Fong holds a B.S. in Business Administration from U.C. Berkeley and a M.S. in Management from Stanford Graduate School of Business.